It happened for the first time that the scientists used 5,700-year-old saliva

to sequence the whole human genome of an ancient women along with the variety of microbes that lived inside her.

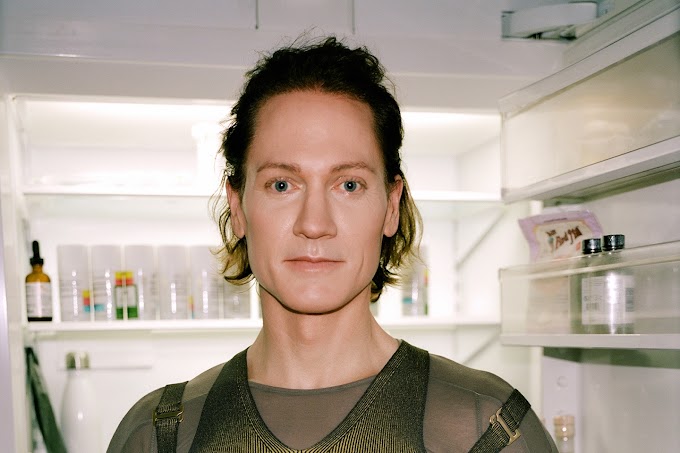

Artistic reconstruction

of ‘Lola’, whose DNA was found in the birch tar. Photograph: Tom Bjorklund/PA

Everyone of us have studied the ancient history in our early education. From where did we get information about them? Fossils, ancient caves and human residuals played an important role over thousands of years in understanding their lifestyle, in order to study the human evolution. It happened for the first time that scientists reconstruct the whole genome of the stone-age women from her salive recovered from her 5,700 year old chewing gum.

She lived near Baltic Sea around 57,ooo years ago. She was lactose bigoted and may have suffered from gum disease. As we also found the DNA of Ducks and hazelnuts, she had recently dined on a meal that included ducks and hazelnuts. She was blue-eyed with dark skin and hair like other ancient Hunter and gatherers.

Scientists named her as "Lola".

She lived near Baltic Sea around 57,ooo years ago. She was lactose bigoted and may have suffered from gum disease. As we also found the DNA of Ducks and hazelnuts, she had recently dined on a meal that included ducks and hazelnuts. She was blue-eyed with dark skin and hair like other ancient Hunter and gatherers.

Scientists named her as "Lola".

This ground breaking research is revealed

in a study

published in Nature Communications- a couple of weeks ago. It marked that for the first time researchers have been able to reconstruct a whole human genome

from the deep past via “non-human material” rather than from physical remains, like bones.

What information did we got?

The scientists had enough ancient DNA to

reconstruct a whole human genome. They concluded that the that the person was female with dark skin, dark hair and blue eyes. She also shows close relationshipwith hunter-gatherers from mainland Europe than those who lived in central

Scandinavia at the time, as per the report in Nature

Communications. It is impossible to know her age, but given that

children seemed to chew birch tar, the scientists suspect she was young.

Further DNA revealed her oral microbiome, the collection

of microbes that live, often harmlessly, in the mouth. Among tens of bacterial

species, three were linked to severe periodontal disease, and Streptococcus

pneumoniae, a major cause of pneumonia. The scientists also spotted the

Epstein-Barr virus, which can cause glandular fever. While she may well have

been ill, all can be present without causing disease or illness.

In addition to Lola’s genetic story, the international team of researchers was also able to identify the DNA of plants and animals she had likely recently consumed, as well as the DNA of the countless microbes that lived inside her mouth—collectively known as her oral microbiome.

“This is the first time we have the complete ancient human genome from anything other than [human] bone, and that in itself is quite remarkable,” says Hannes Schroeder, an associate professor of evolutionary genomics at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute and a co-author of the study. “What’s so exciting about this material is that you can also get microbial DNA.”

While our scientific understanding of the human microbiome is still in its very early stages, researchers are beginning to understand what an important role it plays in our health. Variations in mouth microbiome affects so many things from being susceptible to infection and heart disease to even possibly behavior.

By being able to sequence ancient DNA together with the individual’s microbiome, Schroeder says, researchers will be able to understand how the human microbiome has evolved over time—revealing, for instance, how the dietary shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture thousands of years ago may have altered our microbiome for better or worse.

Stone Age “chewing gum”:

Birch pitch (also called tar), a glue-like substance made by heating birch bark, has been used to fasten stone blades to handles in Europe since at least the Middle Pleistocene (approximately 750,000 to 125,000 years ago). The bead of pitch imprinted with human teeth marks have been found at ancient sites, where archaeologists surmise the pitch was chewed to soften before use. Due to the antiseptic nature of birch bark, it may have also had medicinal properties.

The pitch was radiocarbon dated to around 5,700 years ago, the advent of the Neolithic period in Denmark. This was a time when practices of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers were being disrupted by the introduction of agriculture from areas to the south and east.

Conclusions:

Lola’s DNA shows none of the genetic markers associated with new farming populations entering northern Europe, bolstering a growing idea that genetically distinct hunter-gatherer populations in the region survived for longer than previously thought. Her genome also reveals that she was lactose intolerant, which supports the theory that European populations developed the ability to digest lactose as they began to consume milk product from domesticated animals.

The majority of bacteria identified in Lola’s oral microbiome are considered normal inhabitants of the mouth and upper respiratory tract. Some, however, are associated with severe periodontal disease. Her microbiome also shows the presence of Streptococcus pneumoniae, although it’s impossible to tell from the sample whether Lola was suffering from pneumonia at the time she was chewing the birch pitch. The same goes for Epstein-Barr virus, which infects more than 90% of the world’s population but usually causes few symptoms (unless it develops into mononucleosis).

Seeing the Invisible:

Researchers were also able to identify the DNA of mallard ducks and hazelnuts from the chewed pitch, suggesting that the foodstuffs had been recently consumed by Lola. This ability to isolate specific plant and animal DNA from ancient human saliva trapped in pitch may enable us to “see” dietary habits—such as the consumption of insects—that might otherwise be invisible in the archaeological record, says archaeologist Steven LeBlanc, former director of collections at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

LeBlanc helped usher in the era of extracting human DNA from non-human material more than a decade ago, with a pioneering 2007 study on chewed yucca fibers discovered in archaeological sites in the American Southwest. He believes the toolkit that scientists have now to obtain not only a full human genome, but also microbiome and dietary information from non-human material, will set the new gold standard for understanding how ancient populations grew and changed over time, how healthy they were, and what they subsisted on.

“It's absolutely amazing how fast the field has progressed,” he says. “What we were able to do then compared to what they can do now is just shockingly different.”

It’s also a good reminder that even the most unremarkable artifacts should be studied and preserved, LeBlanc adds, recalling times when he’d show visitors to the Peabody Museum the desiccated, masticated pieces of yucca he researched.

In addition to Lola’s genetic story, the international team of researchers was also able to identify the DNA of plants and animals she had likely recently consumed, as well as the DNA of the countless microbes that lived inside her mouth—collectively known as her oral microbiome.

“This is the first time we have the complete ancient human genome from anything other than [human] bone, and that in itself is quite remarkable,” says Hannes Schroeder, an associate professor of evolutionary genomics at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute and a co-author of the study. “What’s so exciting about this material is that you can also get microbial DNA.”

While our scientific understanding of the human microbiome is still in its very early stages, researchers are beginning to understand what an important role it plays in our health. Variations in mouth microbiome affects so many things from being susceptible to infection and heart disease to even possibly behavior.

By being able to sequence ancient DNA together with the individual’s microbiome, Schroeder says, researchers will be able to understand how the human microbiome has evolved over time—revealing, for instance, how the dietary shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture thousands of years ago may have altered our microbiome for better or worse.

Stone Age “chewing gum”:

Birch pitch (also called tar), a glue-like substance made by heating birch bark, has been used to fasten stone blades to handles in Europe since at least the Middle Pleistocene (approximately 750,000 to 125,000 years ago). The bead of pitch imprinted with human teeth marks have been found at ancient sites, where archaeologists surmise the pitch was chewed to soften before use. Due to the antiseptic nature of birch bark, it may have also had medicinal properties.

Chewed pitch is sometimes the only indicator of a human presence at sites where physical remains are not found, and archaeologists have long suspected that the otherwise unremarkable wads may be a source of ancient DNA. However, we recently extracted the human genome from a stone age chewing gum, along with microbes present in her mouth.

Earlier this year, nearly complete human genomes were sequenced from 10,000-year-old chewed birch pitch originally excavated 30 years ago at the site of Huseby Klev in Sweden. “These artifacts have been known for quite some time,” says Natalija Kashuba, a doctoral student in the department of Archaeology and Ancient History at Uppsala University and lead author on the Huseby Klev study. “They just haven’t been in the spotlight before.”

In the latest study, Lola’s DNA and microbiome were extracted from a chewed bit of birch pitch excavated at the site of Syltholm on the Danish island of Lolland (hence Lola’s moniker). Archaeologists have found evidence for tool making and animal butchery at the Syltholm, but no human remains.

The pitch was radiocarbon dated to around 5,700 years ago, the advent of the Neolithic period in Denmark. This was a time when practices of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers were being disrupted by the introduction of agriculture from areas to the south and east.

Conclusions:

Lola’s DNA shows none of the genetic markers associated with new farming populations entering northern Europe, bolstering a growing idea that genetically distinct hunter-gatherer populations in the region survived for longer than previously thought. Her genome also reveals that she was lactose intolerant, which supports the theory that European populations developed the ability to digest lactose as they began to consume milk product from domesticated animals.

The majority of bacteria identified in Lola’s oral microbiome are considered normal inhabitants of the mouth and upper respiratory tract. Some, however, are associated with severe periodontal disease. Her microbiome also shows the presence of Streptococcus pneumoniae, although it’s impossible to tell from the sample whether Lola was suffering from pneumonia at the time she was chewing the birch pitch. The same goes for Epstein-Barr virus, which infects more than 90% of the world’s population but usually causes few symptoms (unless it develops into mononucleosis).

Seeing the Invisible:

Researchers were also able to identify the DNA of mallard ducks and hazelnuts from the chewed pitch, suggesting that the foodstuffs had been recently consumed by Lola. This ability to isolate specific plant and animal DNA from ancient human saliva trapped in pitch may enable us to “see” dietary habits—such as the consumption of insects—that might otherwise be invisible in the archaeological record, says archaeologist Steven LeBlanc, former director of collections at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Archaeologist Steven LeBlanc

LeBlanc helped usher in the era of extracting human DNA from non-human material more than a decade ago, with a pioneering 2007 study on chewed yucca fibers discovered in archaeological sites in the American Southwest. He believes the toolkit that scientists have now to obtain not only a full human genome, but also microbiome and dietary information from non-human material, will set the new gold standard for understanding how ancient populations grew and changed over time, how healthy they were, and what they subsisted on.

“It's absolutely amazing how fast the field has progressed,” he says. “What we were able to do then compared to what they can do now is just shockingly different.”

It’s also a good reminder that even the most unremarkable artifacts should be studied and preserved, LeBlanc adds, recalling times when he’d show visitors to the Peabody Museum the desiccated, masticated pieces of yucca he researched.

0 Comments